Farm Animals Suffered in B.C. Floods Despite Existing Disaster Management Guidelines

When an atmospheric river hit British Columbia in mid-November, it unleashed record-breaking rainfall triggering devastating floods and mudslides. The provincial government declared a state of emergency on Nov. 17, activating evacuation orders for Merritt, Abbotsford and other communities.

The Sumas Prairie, which lies in the Fraser Valley just east of Abbotsford, is an agricultural hub, housing the majority of the province’s chickens and cows, as well as pig and mink farms. As the floodwaters rose, harrowing images began to circulate on social media and in news reports.

There were submerged barns, cows wading through floodwaters, a helicopter rescue of a pregnant cow and the Canadian Armed Forces relocating broiler chickens from the second storey of barns, while at ground level thousands of birds died from suffocation, from lack of ventilation, or drowning. Industry reports suggest at least 500 cows, thousands of pigs and over a hundred thousand birds perished.

Extreme weather events like the flooding and wildfires in B.C., have occurred in agricultural regions in Australia, the United States and elsewhere, and are likely to become more frequent as the planet warms and the climate changes. Although B.C. farmers are eager to get back to production, the provincial and federal governments must consider that there is more than climate behind these disasters. Industrial-sized confinement farming systems pose insurmountable challenges during hurricanes, floods or wildfires, including significant public health, animal welfare and socio-economic implications.

Our mission is to share knowledge and inform decisions.

Climate disasters aren’t coming, they’re here

When the heat dome settled over B.C. in June, it caused the deaths of 595 people, an estimated one billion marine animals and at least 651,000 poultry. And during the 2019-20 Australian bushfires, amid the coverage for loss of wildlife, few media stories surfaced about the thousands of farm animals “confirmed dead, burned in the fires or euthanized due to their injuries.”

In the U.S., catastrophic hurricanes and floods often grip coastal states and harm farm animals. In 2018, Hurricane Florence led to the deaths of 5,500 pigs and nearly eight million poultry in North Carolina.

The nexus between extreme weather events and animal agriculture is further made relevant because of the farm model. Globally, the majority of poultry, pigs and cows are raised in what are called “concentrated animal feeding operations” (CAFOs).

CAFOs are industrialized operations of thousands to millions of genetically similar animals. These operations confine animals whose vulnerability to disasters varies depending on their species, age or sex — a sow confined to a gestation crate, for example. Adjacent to the barns are stockpiles of manure and burial pits.

My research with Elisabeth Stoddard, an associate professor at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, in Massachusetts, has investigated some of the impacts of climate change — worsening floods and hurricanes — on the animal agricultural sector in North Carolina. In our recent report, commissioned by World Animal Protection, our conversations with producers and other agricultural workers found that the disaster measures were not applicable to their operations. What they meant was, there are too many animals for disaster interventions to work.

Disaster management guidelines

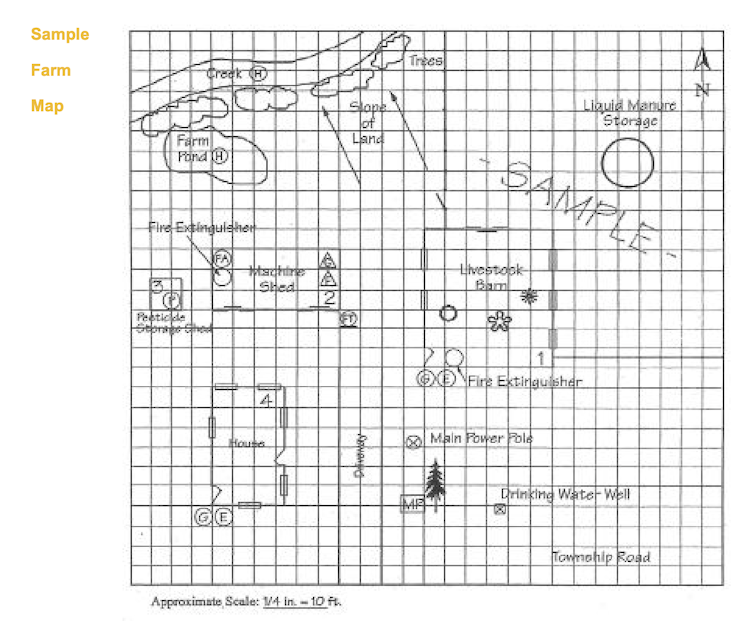

Producers and agricultural workers can refer to disaster management guidelines, often sector-specific handbooks, to prepare for and respond to a range of disasters. B.C.‘s guidebooks offer disaster advice, but do not address the scale of farming, making them unhelpful to producers and useless in their efforts to avert animal deaths and injuries.

As governments, companies and individuals make plans to adapt to climate change, the welfare of farm animals must become a priority that goes beyond updating disaster management guidelines to encourage producers to create farm emergency plans and maps, or invest in insurance.

What can farmers do to protect animals?

For the most part, producers have three options during extreme weather events: leave the animals in place, relocate them to safety or move them to market. The last option remains the most difficult as producers operate on a just-in-time production system with slaughter scheduled according to the animal’s market-ready date.

Sheltering in place remains the most used strategy based on logistical constraints. As for relocating animals, producers retain some resiliency. One chicken producer relocated 40,000 chickens, but had to leave as many birds in a barn when it flooded.

The B.C. beef handbook says “unconfined animals can usually take care of themselves during a flood.” Early accounts from the Sumas Prairie suggest that those animals that were outside, roaming freely, fared better than those securely confined in a building or barn. But many “free” animals still succumbed to flood waters, such as calves that drowned when waters rose past a metre.

Build back better

As the province cleans up, it will need to access and identify farms that require euthanasia for animals with injuries or disease, and mass mortality.

These issues become even more urgent when considering that buried carcasses could contaminate groundwater, produce methane gas or spread pathogens. Despite these challenges, B.C.’s Minister of Agriculture Lana Popham said carcasses may be disposed of in landfills or incinerated.

In the wake of the disaster, B.C. must figure out how it will “build back better.” Here are three things it could do to address climate justice, Indigenous reconciliation and animal welfare:

- Prioritize climate commitments within the province such as those outlined in the B.C. Food Security Task Force’s 2020 report. One of the climate and food security strategies B.C. is pursing is to diversify plant-based production, such as cellular agriculture. This directive should receive real commitment and funding that matches its potential to mitigate the threat of climate, environmental and farm animal disasters.

- Consult and deliberate with Animal Justice following its demands to limit the number of animals on confinement farms and to make animal rescue plans a legal requirement for producers, making them legally binding instead of vague encouraged practices.

- Return unceded land to Indigenous nations. The Sumas Prairie was once a shallow freshwater lake, and is part of the unceded, traditional territory of the Sumas First Nation that, like the water and other beings, was forcibly displaced by colonial land planning, when the lake was drained and isolated from nearby rivers between 1920 and 1924. Unceded land should be returned to the Sumas First Nation to uphold the province’s commitments to reconciliation.